Hinduism, Buddhism, and their development along with their syncretism.

The essences of both religions laid out

The religions of Hinduism and Buddhism have defined Indian culture. They developed along side each other for centuries and both influenced each other sharing many concepts or ideas. While in lay practice people didn’t necessarily separate the two, they both formed unique rigorous philosophical traditions that pushed our understanding of nature and reality as well as our quest for enlightenment.

The Development Hinduism and the Systemization of Vedic Philosophy

Hinduism traces its origin to the Vedas, the central scripture of the Hindu faith as its seen as the source of the shared philosophical revelation of the Hindu religion.

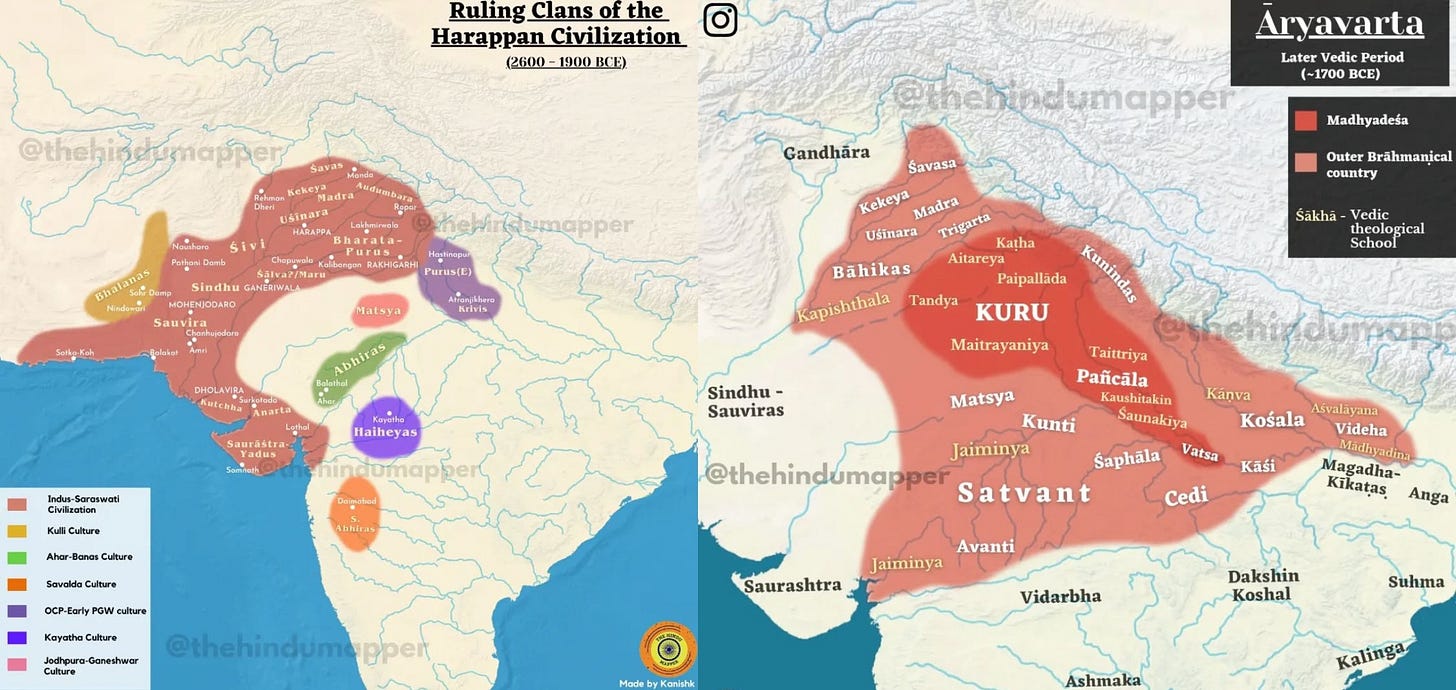

The Vedas were developed & canonized among the Bharata-Purus from the region of the Saraswati river. It was developed by philosopher-priests otherwise known as Rishis from their kingdom, during the later period of the Sindhu-Saraswati Civilization, after the so called Battle of Ten Kings. Prior there were many different ruling clans. The later Kurus belonged to the Bharatas-Purus clan which formed the Kuru Empire.

The ruling clans and the later Kuru Empire

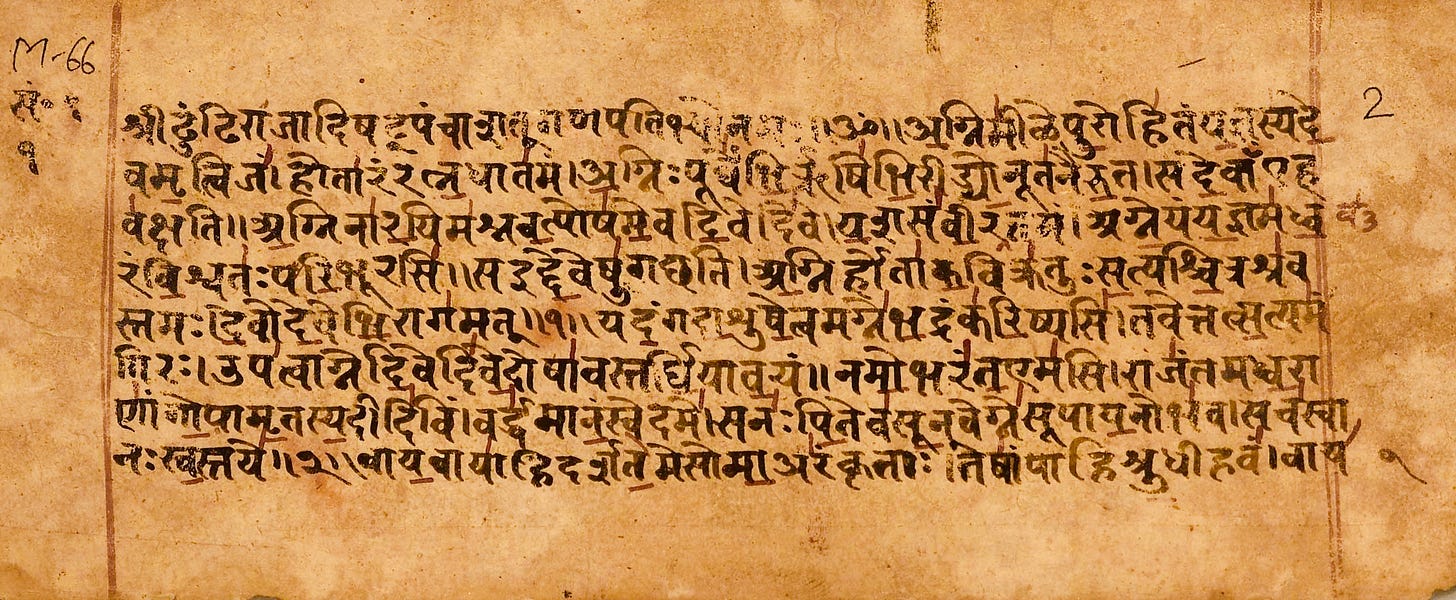

The Vedas are neither a book of commandments nor a sole retelling of stories.

The Vedas itself were practically an encyclopedia of ritual sacrifices/hymns used by Vedic priests, for various deities or situational events. The Vedas are a ritually-centered scripture.

A Vedic Yajna

The stories that happen to be contained in the Vedas were those in praise of deities and their attributes/related legends, but also partially contain accounts of the Bharata-Purus/Kurus as well.

The Vedas also contain a heavy philosophical theme throughout them, centered around a spiritual concept called “Brahman”. Philosophical mantras or passages related to the concept of Brahman came to be known as “Upanishads”. Thus the Vedas in sum are both philosophical revelations on Brahman and various essential rituals.

The Vedas were passed down orally by Hindu priests known as Brahmins. They both practiced the memorization of these Vedas and preformed the rituals of the Vedas for others.

There are four Vedas:

Rig

Sama

Yajur

Arthava

The very many Upanishads are contained within each four.

The Systemization of Vedic Philosophy

In response to differing philosophical perspectives such as Buddhism, Atheism, or other schools of thought, later philosophers of the Vedic tradition developed their own systemized schools of thought in defense of Vedic philosophy & ritual. These schools of thought deal with both investigating and interpreting the Vedas while also defending them & its nature.

It should be emphasized, none of these later philosophers saw themselves as creating “original” philosophies, but rather explaining philosophical points already contained within the Vedas. It should also be emphasized that the Vedas themselves are considered in part developed by philosopher-priests themselves known as Rishis. It is thus necessary to say that the Vedic Rishis were India’s first recorded philosophers and original developers of the Vedic lines of philosophy.

The Brahma Sutras are a later philosophical scripture by Badaryana which explores the concept of Brahman in the Upanishads, laying the foundation for the Vedanta school. As the concept of Brahman is the over-arching theme of the Vedas, the study of Brahman inspired the name “Vedanta”, which simply means “conclusion of the Vedas”

Vedanta (Uttara Mimamsa) School

Vedanta is one of two schools of Vedic philosophy. Focusing on the Upanishadic portions of the Vedas & theology of Brahman. This is also known as the “Jnana Kanda” or ‘the knowledge portion’ of the Vedas. Also can be known as “Uttara Mimamsa”, or ‘latter insight’.

The concept of Brahman in the Vedas is actually quite simple to understand: its the spiritual/metaphysical origin of everything including the many deities, & is infinite & formless in nature.

However, a very important part of the Upanishads & theology of Brahman is entirely disputed: what is Brahmans relation to an individual’s soul (Atman)? This question inspired much debate among Hindus themselves, and inspired the very many sub-schools of Vedanta!

•Advaita

Adi Shankara

First and among the oldest is Advaita Vedanta. While attributed to Adi Shankara as its founder, this philosophy is much older as Shankara himself belonged to a line of Advaita Gurus.

Advaita Vedanta posits the idea that an individual soul only exists in idea or expression much like the “forms” of the material world. Thus ultimately there is no individual soul, just the encompassing, omnipresent, spirit of Brahman which everything belongs to. This in turn leads to a panentheistic conclusion of Brahman’s nature.

•Vishishtadvaita

Ramanuja

Ramanuja of the Vishistadvaita sub-school disagreed. He posited the individual soul does exist metaphysically like Brahman, but is both contained within Brahman and shares the quality of Brahman. In many way’s Vishistadvaita both affirms Brahman’s panentheism & our individuality in this world.

•Dvaita

Madhvacharya

Madhvacharya disagreed even further. He instead posited the soul exists and that the material world and its material forms exist separated and not contained within Brahman. This lead to a dualistic & heno-theistic interpretation of Brahman.

On their views of Moksha:

Advaita philosophers belonged to the idea of “Jnana Yoga” or in English, “Method of Knowledge”. This is in reference to the idea that only through knowledge first can one achieve enlightenment, and ritual duty was secondary to Jnana. They believed Moksha (enlightenment) was more of a state of mind, seeing past the illusion of duplicity. Thus they believed Moskha was to be achieved in your current life, rather than after death. Furthermore for the nature of Samsara (the world and it’s manifestation/reincarnation): they believed Samsara as a function of Brahman. Therefore Samsara was ultimately inescapable, reiterating the idea of Moksha in this life and simply as a state of mind.

Dvaita philosophers pushed the idea of “Bhakti Yoga” or “Method of Devotion”, as a means to achieve Moksha. As Brahman is separate from material reality and separate from the individual’s soul, Brahman thus belongs on a plane of his own. Thus he can only be sought after to have union with, through devotion. To them the Vedas were given by Brahman, and ritual service and devotion are our means of union. To them union can break one free from Samsara - as Brahman is outside of Samsara to them, though this can happen only after death, when your individual soul is no longer bound to your body.

(Purva) Mimamsa School

The Mimamsa Sutras were written by Jaimini. He was a student of Badaryana, the founder of the Vedanta School.

The Mimamsa philosophy on the other hand actually seldom deals with the concept of Brahman. This isn’t to say Mimamsa philosophers denied Brahman (they saw the Upanishads as infallible), but rather they just focused heavily on the ritual portion of the Vedas. This was also known as the “Karma Kanda” (action portion) of the Vedas, or “Purva Mimamsa” (former insight). Mimamsa philosophy was therefore named after that.

Mimamsa philosophers on one hand dealt with right interpretation of rituals and on the other hand, the reasons for ritual conduct.

To the Mimamsas, the reason for ritual action was that its the way to live harmoniously, morally, & virtuously. Living otherwise would lead to disharmony in nature & disrespect, leading to bad karma or “sin”. Thus to the Mimamsas one must engage primarily in proper duty, and proper duty was typically seen as selfless in nature.

Arjuna of the Bhagavad Gita is persuaded to follow the ideals of Karma Yoga by Krishna

This idea lead to the concept of Karma Yoga or “Method of Action”. This was synthesized with Jnana or Bhakti depending on the respective Vedantic philosophy. Karma Yogis sought to live selflessly and with virtue and sourced their morality on Vedic principles.

To the Bhakti interpretation, this meant that Karma Yoga was itself a form of devotional service (Bhakti) to Brahman, meanwhile the Jnana interpretation meant that right knowledge of Brahman naturally brings one to the conclusions of Karma Yoga.

Smarta Tradition

Renunciation and Ritual

Both Mimamsa & Vedanta philosophies were not opposed to each-other. They were synthesized as being part of the Vedic tradition & were complementary. Vedantic philosophers like Adi Shankara for example, saw their philosophy as a completion of Purva-Mimamsa. The synthesis of both philosophies of Vedanta & Mimamsa for example was known as the Smarta Tradition.

Smarta can honestly be used interchangeably to the “Vedic tradition”, or even “Hinduism” as Hinduism after all is simply the culmination of these two philosophical schools.

However theres a real reason why “Smarta” was categorized as a concept to begin with. Brahmin priests who solely belonged to Vedic ritual traditions were known as “Smarta Brahmins”.

Agamaic/Tantric Tradition

Smarta Brahmins were in contrast to Brahmins who followed the ritual Agamas.

This is where we get to the many Tantric traditions of Hinduism.

Following the development of Vedanta and its various sub-schools, many deity-specific traditions developed across India!

I guess the closest thing I can relate this to is the “Mystery Cults” of Ancient Rome.

These esoteric traditions developed around a handful of deities. Essentially a handful of deities became very popularly seen as ‘absolutely synonymous’ to the concept of Brahman itself and were then seen as the primary pathway to liberation via Bhakti Yoga. This is also known as the Bhakti Movement (which honestly was not a “movement” at all but rather a development).

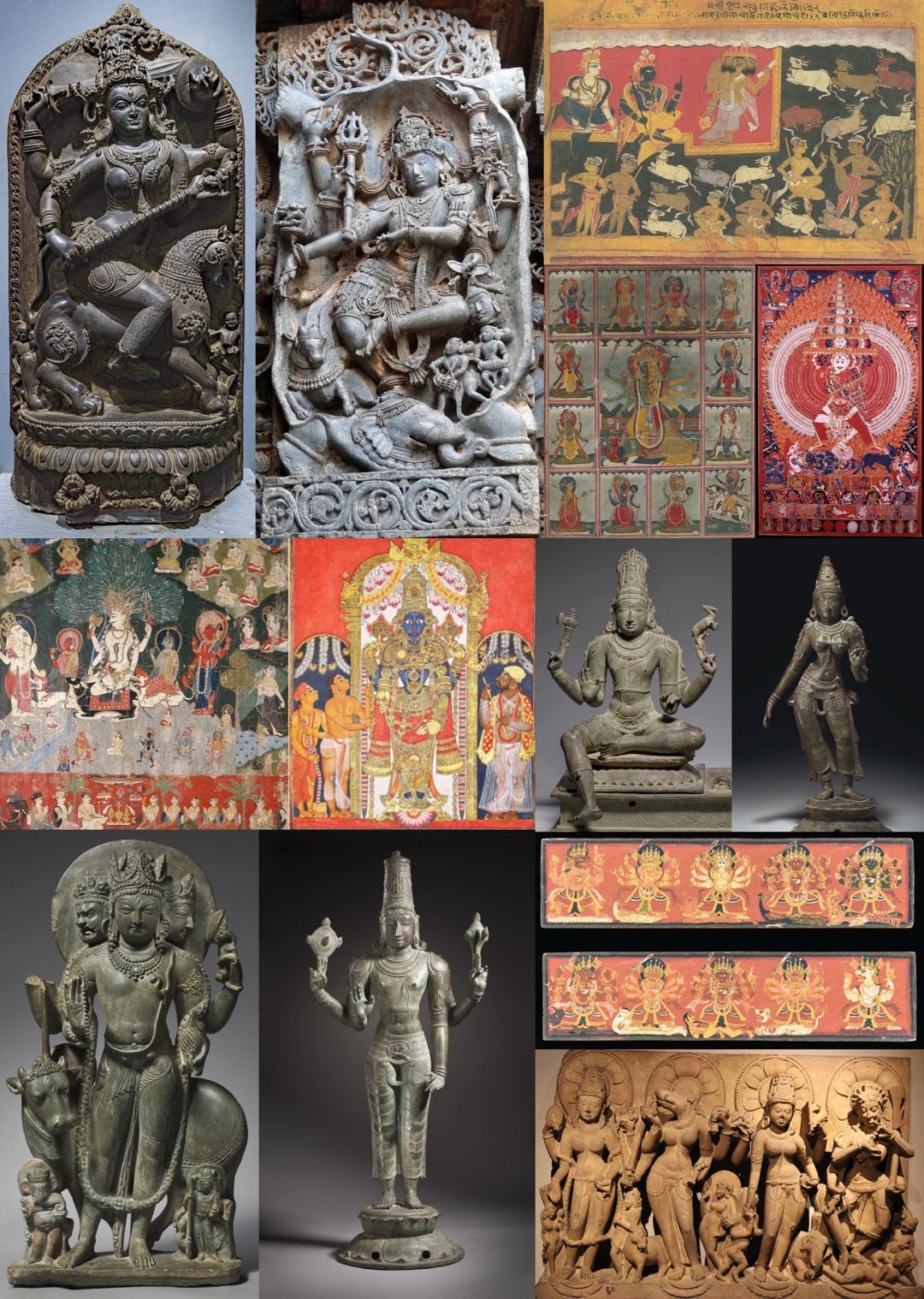

Tantric Hindu art

The Agamas were the many ritualistic scriptures and Yogic/Tantric practices that developed in this period. Priests that specialized in these rituals were Agamic Brahmins. Temples associated with the Agamic traditions were also very often built.

The most popular Agamic Deities and Traditions were:

Shaivism (Shiva as Brahman)

Vaishnivism (Vishnu as Brahman)

Shaktism (Shakti, aka feminine energy as Brahman)

Saura (Surya as Brahman)

There are many, many sub traditions of these traditions depending on the region of India they developed in or their peculiar Vedantic interpretations. For example, there are different Advaita, Vishistadvaita, and Dvaita Shaivist traditions (likewise for other deities). All such Agamas are heavily influenced by Vedantic thought.

The Development of Buddhism

Siddhartha Gautama, aka the Buddha

Buddhism was known as a Sramana (seeker) philosophy, alluding to the idea the philosophy was found by seeking elsewhere than the Vedas. It was founded by the philosopher & ascetic, Siddhartha Gautama aka the “Buddha” around the region of Kosala in the Shakya feudatory during the Mahajanapada Era (c.6th century BC). It was a strict renunciate philosophy, renouncing concepts of duty, the world, and worldly life, in attempts to end suffering completely.

Kosala/Shakya seen in the center of many kingdoms

While Buddhism generally accepts some Vedic concepts such as Dharma, Karma, & Samsara, it disregards the Vedic rituals and also the Vedic concept of Brahman.

Many people suggest the Buddha didn’t explicitly deny Brahman/the concept of Atman, which is true as he had avoided such metaphysical speculation. However he did explicitly state that the soul/spirit is impermanent, thus contrasting Buddhism from Vedantic thought, as Brahman/Atma is permanent and unchanging.

The Buddha’s philosophy of non permanence and “paticca-samuppada”(dependent origination), set the stage for a different philosophy compared to the Vedantic tradition. Dependent origination implied that matter & phenomena exists as an intricate web of dependencies rather than arising from an independent source (such as Brahman).

Furthermore the Buddha implied full renunciation alone can free one from Samsara - this also implies a denial of Brahman, as in Vedantic philosophies Samsara is a result of Brahman, and one can not alone free themselves from it. (And in Advaita theres no actual “freeing” from it at all).

There were many early schools of Buddhism which debated the absolute nature of impermanence & dependent origination and also as a result even free will. They also debated the identity of the Buddha as either someone transcendent or mundane. Most of these schools either went extinct or evolved into or influenced the later sects.

For the most part two major schools developed later on from the first Buddhist schism:

Theravada built out of the early Sthavira Nikaya sect

Mahayana built out of the Mahasanghika sect

Both of these sects were also influenced by the Second Buddhist Schism, which resulted out of opposing views on the authenticity of monastic codes. There was the conservative Mahavihara and the liberal Abhyagiri doctrines.

Theravada Buddhism

Buddhaghosa, an important Theravada Philosopher

Theravada Buddhism sources itself from the Pali Canon. Written in the Pali language, it contains many of the Suttas (sayings) of the Buddha.

Theravada was influenced by some of the Abidharma doctrines of the early Buddhist schools. This implies the Buddha was a mundane man, downplaying ideas of transcendence and treating the philosophy from a systematic lens.

Theravada was also influenced by the Mahavihara doctrines in the second schism, which sought to keep authenticity within the monastic order. It was more or less a conservative reaction to limit expanding and new monastic traditions.

Theravada lacks a priesthood. It’s entirely a monastic order and is made up of monks or nuns. It takes on a strict monastic interpretation, assuming that a complete rejection of Samsara leads one to Nirvana.

Theravada also doesn’t see the various deities as Buddhas or Bodhisattvas on the same level as Siddhartha Gautama himself. Instead they are more mundane and are treated solely as guardians.

Mahayana Buddhism

Nagarjuna, a major Mahayana philosopher

Mahayana Buddhism sources itself from the Buddhist Agamas (completely different from the “Hindu Agamas” despite the name). This canon is a Sanskrit as well as a later Chinese translation of the early Buddhist Suttas. Its parallel to the Pali Canon but does have its slight variations.

Mahayana was partially influenced by early Yogacara thought. Yogacara ideas assume sentience is outside of one’s control (life is the result of its own continuation). To them, concepts of reincarnation imply that freedom from Samsara is impossible unless all sentient beings seek Samsara. Thus Mahayana takes on that mission, to lead everybody to renunciation.

Mahayana thus has influence from the additional Mahayana Suttas which the Theravada school rejects. The Mahayana Suttas also contain the influences of Madhyamaka teachings.

The Madhyamaka teachings are the ideas of the Two Truths Doctrine, Sunyata, Buddha-Nature, and the Middle Way which builds upon the “Bodhisattva” doctrine.

The Two Truth’s Doctrine and Sunyata are complimentary. The Sunyata is the concept of an “ultimate nature of emptiness” which is the nature of everything, as everything is impermanent. As a result nothing contains a fixed essence. Yet at the same time everything is obviously apparent and seemingly carries form. Hence two-truths.

Manjushri Bodhisattva

The ideas of Buddha-nature, the Middle Way, and the Bodhisattva doctrine are also complimentary of each other. Everything carries empty nature (Sunyata), which is the nature of a Buddha, and many Buddhas spawn, as the Buddha’s nature is transcendent. This is to liberate all beings. In this, the Buddha becomes more of a preacher of a mission than a man who simply achieved freedom from samsara.

So, samsara and liberation are not as heavily separated, one should stay in samsara out of compassion for all sentient beings and to preach the message of Nirvana, as only then can true Nirvana be achieved. That is to embrace the Middle Way or “Path of the Bodhisattva”, and one who does so is a Bodhisattva.

Many Bodhisattvas are revered along with many deities who are seen as carrying Buddha-nature and teaching enlightenment.

Because Mahayana was influenced by more liberal Abhyagiri doctrines during the second schism, strict monastic codes simply didn’t matter as much. Furthermore the Bodhisattva ideal implied a need to spread the doctrine and include more people. It was thus much more influenced by Hinduism.

As a result much like Hinduism, in Mahayana there is tantric traditions & priestly communities for those tantric traditions. Many such tantric traditions share overlap in influences with Hindu tantric traditions. There are many more Yogic practices among Mahayana Buddhism than in Theravada.

Tantric Buddhist art

In many ways Mahayana shares some similar worldliness/duty concepts with Hindu schools and similarities can also be drawn between Karma Yoga or the path of the Bodhisattva (though ultimately their goals are different). At the same time it’s tantric traditions share meditative practices, rituals, and other concepts to Hindu Agamic rituals.

While both Theravada & Mahayana differ as schools of thought, there is still much overlap by them as they both seek to simply interpret the same Buddhist canon, defining what a Buddha is, and seeking how to ultimately achieve enlightenment. Mahayana simply builds upon it in a much broader context.

They both consider themselves as authentic to the true teachings of the Buddha and at the end of the day they see themselves as both followers of Buddha-Dharma.

Both Hindus and Buddhists also have large cosmological & story telling traditions.

Among Hindus this is seen in the various Puranas & Itihasas, meanwhile Buddhists have the Jataka Tales & other various Suttas or Tantras. The many deities seen in both are often shared among Hindus and Buddhists.

Why are Hindus & Buddhists seemingly polytheistic?

Lakshmi & Vasudhara

Hindus are polytheists (revering many gods/paths) because, well for one, the Vedas are very polytheistic in nature. Praising many Gods, describing them in imagery with detail.

Advaita sees the Gods as animate functions of nature & reality as they are underlied by conscious force (Brahman). Thus rituals as a form of communication and reverence for them, and as a means to keep harmony in the world, as Moksha doesn’t necessarily free one from Samsara in Advaita. Thus harmony is important since worldliness is embraced. This is the complete synthesis of Mimamsa and Advaita which is the basis for the Smarta tradition.

Dvaita sees the pluralistic nature of the Vedas in a henotheistic fashion, where the many Gods are lesser incarnations of Brahman (often synonymous with Vishnu). In this way the Gods are various guiding paths to the end goal of enlightenment, speaking to people in diverse ways and circumstances. Rituals are seen more as a function of devotion.

Also the Hindu Brahman as a concept doesn’t have any self-centered goals, forms, nor has any wants or needs, and therefore lacks the ability to “command” monotheistic worship. It is a formless, philosophical concept. Thus there is nothing to suggest you must worship or revere things a certain way, long as what you revere is moral and virtuous (and leads you to the end goal of both philosophies) then theres no problem.

In Mahayana Buddhism the various Gods are typically powerful and magical Bodhisattvas in nature, and are identified with in tantric worship to emulate and identify with. In many ways Mahayana Bodhisattvas are like an elaborate group of saints, and magical saints.

Also, It should be noted that theres nothing to suggest that someone can’t revere more than one thing. Do you have to love only your mom or can you also love your dad or even many others? Must you only revere the sun & not the moon? Theres no reason to limit your reverence. Good can be found everywhere in nature, and your love for good things can be endless.

Problem of evil explained

Why would Brahman create a world with evil in it? Well by law of perception, as long as God exists and perceives (as he is pure consciousness by nature), reality must exist as something has to be perceived by consciousness, this is unavoidable. Hindus argue the universe is a “play” (lila) however as God ultimately lacks ego and can not have reason to create the universe. In other words, theres no genuine reason for existence, but truth & purpose (realization of or devotion to Brahman) is the means for good in this existence.

If humans believe there is good and evil we must first interpret what the nature of goodness is and nature of evil is. Both Hinduism and Buddhism identify the materiality of existence, ego, and temporal nature of things as the root cause of suffering or evil.

Thus Hindus see identification with God as necessary to overcoming evil by seeking oneness, and harmony. Proper action to facilitate social harmony is argued and debated in the Hindu Dharmashastras, the Hindu law tradition.

As for Buddhists, reality also is destined to exist because of the nature of dependent origination. Everything must exist because everything depends on externalities to exist, ad infinitum. There is no general beginning or end to reality.

However like Hindus they believe material causes to be the root of evil, but unlike Hinduism, Buddhists seek to ultimately reject it, and seek ultimate cessation of worldliness & attachment. Thus through the rejection of the material world and ego (evil) they naturally find peace in cessation (good).

______________________________________

Both Hinduism and Buddhism have defined South Asian culture for centuries. It is these great traditions which Indian culture belongs to.

https://substack.com/@deepenmehra1111/note/c-102518179?r=5cafb4&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action

Hy kindly check this article, its about krishna and rama , and why they were depicted as blue in colour.

it is not terribly unlikely that an Iranic people migrated so far east into India, as many Iranic tribes had by the 5th century BC already made incursions into the subcontinent — be it on their own or in collaboration with the Persians. The Sakas had proven unimpeded by the harsh geography of South-Central Asia when they crossed the Tian Shan mountains into China, becoming the Wusun and Yuezhi.

The second point of note is the mention of incest among the Shakyas. This was a practice associated by Indians and Greeks alike with the Iranic peoples, albeit mostly the Persians and mostly after certain religious corruptions spurred on by the Achaemenid royal court. Practices like this were shunned by the Vedic Aryans but appear in reference even to the lineage of the Buddha himself. Reading Witzel’s religious arguments for an Iranic origin of the Buddha, I can’t say I’m terribly convinced. He mentions some vague mantras shared by Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, as well as the focus on the afterlife in both, but I think the former is meaningless and the latter is not that meaningful since such ideas of heaven and hell had already existed in the Brahmanical religion. In some ways Zoroastrianism is actually more like the opposite of Buddhism — it is anti-ascetic, it posits a linear timeline with a (presumably) final victory of goodness over evil, and it focuses very little (at least exoterically) on any sort of enlightenment or union with the absolute.

However, a lot of these differences may have already existed at the beginning of the Vedic-Ahuric schism. We know that for some reason, the Rigvedic tribes decided to call the deities they worship Devas, and the deities they don’t worship Asuras. While the Iranians called the deity they worshipped Ahura, and the deities they did not worship Daevas. There are clearly deities shared between the two cultures, like Mithras. Tangentially, Æsir might be cognate with Ahura/Asura. Some suspect that there was a sort of religious falling out between the Indo-Aryans and the Iranic tribes because of this.

One could perhaps make the argument that Buddhism is actually more similar than Hinduism to Zoroastrianism in some regards. The strongest similarities are observed in the Zurvanite tradition of Zoroastrianism, which posits the existence of a transcendent being beyond Ohrmuzd and Ahriman called Zurvan, who is identical to eternity (which, in a metaphysical sense, is different from simply being a “time god”). You can more generally argue that the lack of a particular identity associated with an ultimate reality is itself a difference between Zoroastrianism and Hinduism that could generate the synthesis of Buddhism. And this is only considering Zoroastrianism, something most Sakas probably didn’t practice earnestly. What may be more relevant is the religion of the Scythians, Sauromatians, and Alans. Interestingly, the Scythians were said to have a Heraclitan view of the world, with the most primordial element being eternal fire symbolized by the goddess Tapati. It is this view, in the Greek context, which is most often brought up in discussions about similarity with Buddhism. Heraclitus’s eternal flame is parallel to the Buddhist understanding of Sunyata. It isn’t empty in the sense that it is literally nonexistent, it is empty in the sense that it cannot possibly be attributed static qualities or form. When Heraclitus describes the fundamental substance as fire, he is similarly saying that static objects only exist secondarily to an infinite kinesis, a fire which is at every single moment flickering and embodying something different.